When I was 17, I got “The only constant in life is change” tattooed on my right forearm, both as an homage to my late grandfather who allegedly repeated this phrase a lot and a reminder to myself to be open to change (especially in a post-COVID world).

It’s kind of funny how important this notion has become for me. I really do believe with my whole heart that everything in this world is (meant to be) dynamic, fluid, and ever-changing.

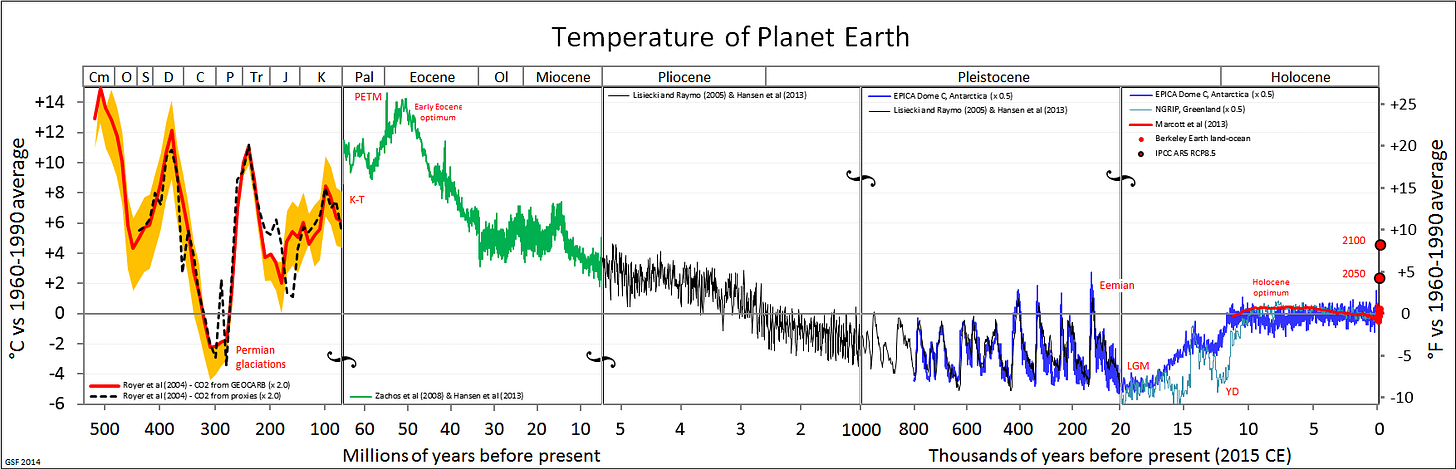

A good starting point to think about this concept is the Earth itself. Think about how the continents move centimeters in different directions every year and the long term implication of that as Continental Drift. If we zoom out and look at the planet in all of its 4.5 billion years of existence, something is certain: it has changed again and again and again, and will continue to change until the sun explodes.

Something that is perhaps a better example, more apparent and visible to us, is how rivers carve out paths and actively change landscapes as they erode and deposit sediment. (Fun fact, this is actually why some US states have really weird borders! Here’s an interesting article on that: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/147242/how-rivers-shape-states). Even within the span of decades, landscapes can drastically change due to the unpredictable and ever-changing courses of rivers.

If we really want to zoom in relative to ourselves, we can look at our own bodies. From birth to death, our bodies are constantly in flux. Babies are born with around 300 bones, and by the time we are adults, we have 206. We loose our 20 baby teeth as we get older, which are gradually replaced by 32 adult teeth. As we approach old age, our bodies continue to change. Wrinkles form in our skin, caused by the breakdown of collagen and elastin. Our immune systems become weaker, our joints stiffer, and our hair thinner and grayer. The human body is never a consistent thing — it is always changing.

Even more important are the changes we enact on our own bodies. Getting a haircut every month, trimming and shaving facial and body hair, punching holes through our ears: our bodies are never as they were “originally,” and they are not meant to be. The beauty in living and in being human is the ways in which our bodies change and the ways we can be the authors of that change. To be human, to inhabit a human body in any capacity, is to experience constant physical, psychological, and emotional transformations as we exist and grapple with the world around us. Our body’s ability to adapt and be changed is deeply embedded in our evolutionary history.

Being transgender and transitioning is, at its very core, in the most simple terms, an embrace of this ability to adapt, an unabashed acceptance of our humanness and the body’s innate ability to be changed. Hormone Replacement Therapy, gender-affirming surgeries, and the changes that transpire as a result of medically transitioning aren’t radical: it is simply another way that the body is able to be changed.

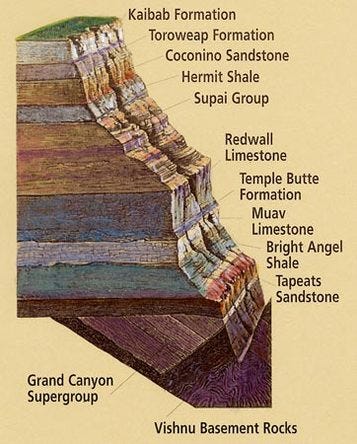

Something that feeds off of this idea is the idea of accumulation. Accumulation is defined as the gradual gathering of something. To go back to our example of the Earth… what is it if not a record of billions and billions of years of geographical and geological accumulation?

In archaeology, this idea of accumulation, or adding onto what already exists, is especially present. Civilizations tend to build on top of existing structures out of convenience as culture and technology changes. (Here’s a great video on this topic: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wyTOYEk_Z2Y&t=1s). A lot of churches across Europe have been built over older churches, their original architecture still partially intact underground. Here in the US, Seattle is a great example of a more modern city that has been built directly on top of an older version of itself.

Accumulation is a natural part of our world. It is how time and events are knowingly and unknowingly recorded, even in our own bodies. Wrinkles and scars, for instance, slowly accumulate on the body, evidence of the lives we have lived that we carry with us. Everything, from the ground we stand on to our own bodies, carry visible and invisible indicators and records of the past.

Parallel to this is Judith Butler’s theory of identity assimilation, which asserts that gender is not a pre-existing, inherent quality but instead constructed and maintained through repeated performances and social norms. She argues that gender is created and defined through the collective accumulation of those repeated actions. “We dress in certain ways, do certain exercises at the gym, use particular body language, visit particular kinds of medical specialists, and so on. Through some repetitions, gender is reinforced, layer by layer.”

In transitioning or identifying as transgender, it is often seen as the death of one person and birth of another, a myth that has been created and perpetuated by cis-heteronormative medical institutions to more easily understand trans identities. The definition of transness as “being born in the wrong body,” as well as all other diagnostic criteria for transsexuality, was thought up by wealthy white cis-het men in the 1960s (see Harry Benjamin’s 1966 “The Transsexual Phenomenon” and Sandy Stone’s “The Empire Strikes Back” essay). It is in these ideas that we begin to see trans people become inculcated with internalized transphobia, as they understand their entire body to somehow be a mistake and their pasts something they must rectify.

There are the expectations that trans people scrub themselves of any and all nuance, reposition themselves within the existing gender binary, and most importantly, pass and become undetectable. What a gender therapist wants to hear, at least to diagnose someone with gender dysphoria, is that their goal is to become as close to a cisgender man or woman as possible. Yet, in this, there is an understanding that they will never quite be the real thing. The constructed penis or vagina will never look quite right. The chromosomes will never match up.

The goal in this all is to put trans people into a cis-heteronormative box and have them live in shame of their “deceptiveness” and inability to be “real" (cis) men or women. The goal is to make trans people think that being trans means to be miserable. Because they will never have a “real” penis or vagina, they will never have the XX or XY chromosomes, and they will forever have to be perpetrators of “deception.”

The entire pathological construction of transgenderism (formerly transsexualism) is, in short, bullshit. Identity, especially something as complex and relative as gender, isn’t something you can neatly write a list of criteria or order brain scans for. Things have changed since the criteria was first introduced in the 60s (for instance, heterosexuality was a necessary part of the criteria to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria until the 80s), but not nearly enough.

I first started seeing a gender therapist in 2018 after begging my parents. I spent a year doing assessments. This included everything from drawing pictures of what I wanted to look like to hyper-analyzing every aspect of my childhood. A big part of it was trying to pinpoint why I was trans, to somehow find a specific, singular moment upon which my transness hinged. What toys did I play with? What clothes did I wear? Who did I sit with at lunch in elementary school?

Looking back, I have a lot of resentment over the fact that I spent so much energy and time having to prove who I was to other people. For so long, I was conditioned to believe that there was no hope for me, that I would be stuck in an alien body forever regardless of HRT or gender-affirming surgeries. I now wonder, if perhaps someone had reframed it for me, if perhaps there wasn’t this weird box that society, medical institutions, and therapists placed trans people into as a way to try and understand it for themselves, maybe I would’ve been kinder to myself. Maybe I wouldn’t have been convinced my goal was to be a cis man (which, now, it isn’t!). Maybe a lot more young trans people would not try to mold themselves to appeal to unattainable cis-heteronormative expectations and be kinder to themselves.

There needs to be a fundamental shift in how we understand, study, and talk about being trans. It needs to be reframed, not as an attempt to assimilate, not for cis people or their understanding of us, but for trans people, for ourselves.

…

Just like anyone else, trans individuals are a collection of every single version of themselves that has ever existed, or in the words of Alberto Ríos, “All the yous that you have been” (“A House Called Tomorrow”).

Transness is an alternative type of accumulation.

It is crucial that we begin to widely understand being trans as adding onto an existing identity rather taking away from (augmentative rather than destructive). Too often we think of being gay or trans or any other queer, non-normative identity as a deprivation, something that robs of us of having worthwhile, full lives; something that is the worst thing we could possibly turn out to be; and something that means any past version of ourselves aren’t worth honoring or respecting. In reality, queerness is beautiful and natural. Embracing the ability of our bodies to be changed and having the autonomy to enact those changes is sacred and unique to the human experience. Like a river carving a canyon out of a rocky landscape, we are simultaneously both the river and rocks.